“Once I read in a book that villains have lost their romantic dimension; today they hide behind crisp suits and wide smiles”. This sentence no longer sounds like a literary exaggeration, but rather a simple observation. Evil, in contemporary narratives, doesn’t need to stand out. It doesn’t seek to shock. It prefers to blend in.

For decades, villains were recognizable. They had intensity, passion, ideology. They were theatrical. This exaggeration offered something precious: distance. Evil could be placed outside the ordinary person, and therefore outside their responsibility.

Today, that figure seems outdated. Not because evil has disappeared, but because our understanding of it has changed. Contemporary thought—and psychology in particular—has stopped seeing it as an exception and has begun to view it as a possibility. Not as an identity, but as a condition.

The most unsettling characters are not those who ignore right and wrong. They are those who know it. They can name it, explain it, invoke it. What is missing is not morality, but empathy. Morality functions without weight, without cost, without inner engagement.

From this arises a new form of evil: quiet, functional, socially integrated. It doesn’t need ideology or passion. Absence of connection is enough. Evil doesn’t shout; it organizes.

Perhaps that is why these narratives unsettle us. They offer no catharsis. They allow no easy condemnation. They do not leave the reader or viewer comfortable, because they show nothing foreign. They show something possible.

History, after all, moves in cycles. There are periods when morality approaches humanity and gains a face. And others when it recedes, becomes abstract, almost technical. In those moments, evil doesn’t need to be spectacular. It is enough that it is orderly, disciplined, reasonable.

Perhaps, then, villains haven’t lost their romanticism. Perhaps we have simply lost the need to see them as myth. And this loss, as uncomfortable as it is, says something disturbingly true about the way a society learns—and forgets—to connect morality to human beings.

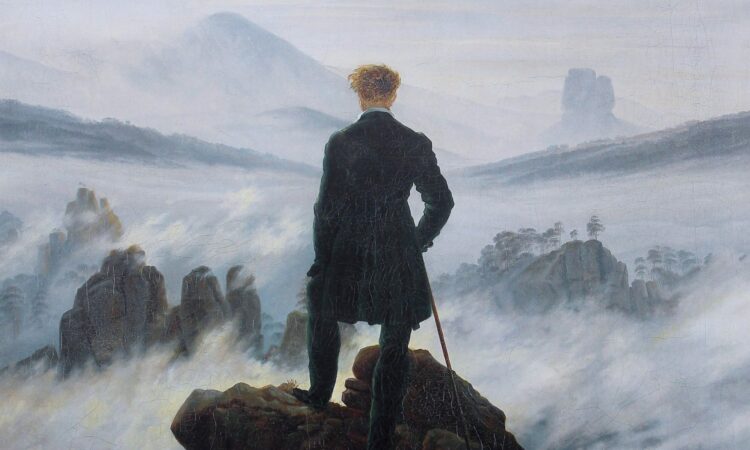

(Cover photo: Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818, oil on canvas. Public domain)

🎄 Support Florence Daily News this holiday season

If you value our work, please consider supporting Florence Daily News this Christmas.

We’re an independent news site — free from paywalls and intrusive ads — committed to offering clear and reliable reporting on Florence and Tuscany for everyone.

Your contribution helps us remain independent and continue telling the stories that matter.

As a small thank-you, supporters this holiday season will receive an original photograph of Florence — a simple, meaningful gift to celebrate the city we all love.

🎁 Donate securely via Stripe below and make your gift count for good journalism in Tuscany.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyEirini Lavrentiadou is an actress and singer, born in Thessaloniki in 1992. She lives in Florence, where she trained at the city’s Theatre Academy and the Fiesole School of Music. She has performed in classical Greek and European plays, worked with international directors and companies, and appeared in concerts ranging from opera to jazz. She contributes to Florence Daily News as a writer.

Discover more from Florence Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.