In the aftermath of Renee Nicole Good’s killing, much of the public debate has settled around an apparently inevitable question: why did the ICE agent fire his weapon? Explanations arrived quickly and in abundance. Fear was cited, along with operational stress and errors in judgment. Some pointed to misogyny, others to the agent’s personal prejudices. Understanding the motives of the perpetrator is undoubtedly relevant, but there is a risk in stopping there.

When attention remains fixed on the inner life of the person who commits violence, the structure that makes that violence possible tends to fade from view. The act appears as an individual accident rather than the outcome of a system. And yet the more difficult—and perhaps more urgent—question concerns the institutions that grant coercive and lethal power to individuals who are not always capable of exercising it with discernment.

Good was a woman, she was gay, and she was present as a legal observer. These characteristics have often been invoked to explain why her behavior may have been perceived as provocative. But focusing on the victim’s identity risks producing the same effect as focusing on the perpetrator’s psychology: it diverts attention away from the power structure within which the killing took place.

Jobs of authority are not merely jobs. They offer the capacity to impose one’s will on others and attract people driven by very different motivations. Training and protocols do not automatically guarantee emotional balance, tolerance for challenge, or the ability to navigate ambiguity. When a subjective perception of threat becomes sufficient justification for the use of force, the problem is not merely individual—it is institutional.

Naming misogyny or prejudice helps identify real dynamics, but it is not enough. The central question is not only why Renee Good was killed, but why the power to kill was entrusted to someone who proved unable not to use it. This question runs through the entire chain of authority, from the agent on the ground to the political leadership that shapes the climate in which such power is exercised.

Perhaps, then, the point is not to stop looking for explanations, but to shift our gaze. As long as we continue to explain violence solely through individual motives, we will continue to treat it as an exception. Looking at institutions instead means recognizing that what appears to be an error is, at times, a signal.

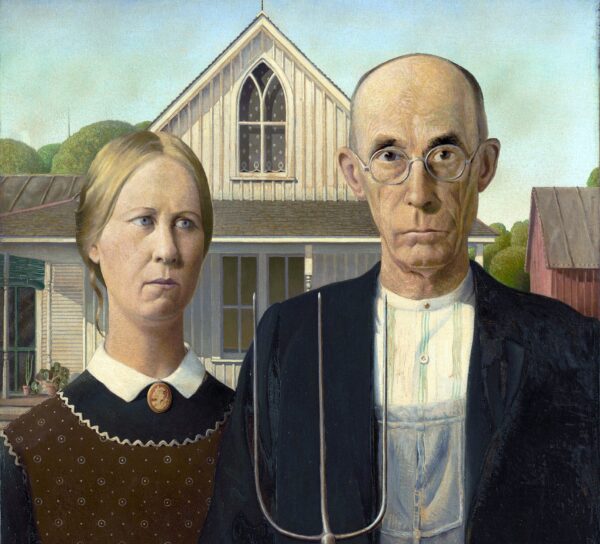

(Cover photo: American Gothic by Grant Wood, Public domain)

❤️ Support Florence Daily News

If you liked this article, please consider supporting Florence Daily News.

We are an independent news site, free from paywalls and intrusive ads, committed to providing clear and reliable reporting on Florence and Tuscany for everyone.

Your support — whether a one-time gift or a regular contribution — helps us stay independent and keep telling the stories that matter.

Donate securely via Stripe below.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyEirini Lavrentiadou is an actress and singer, born in Thessaloniki in 1992. She lives in Florence, where she trained at the city’s Theatre Academy and the Fiesole School of Music. She has performed in classical Greek and European plays, worked with international directors and companies, and appeared in concerts ranging from opera to jazz. She contributes to Florence Daily News as a writer.