In the heart of a square once ruled by Renaissance ideals of power and perfection, a golden statue of an ordinary woman is stirring up extraordinary debate. Her presence is quiet, but the questions she raises about race, gender, and visibility in public space are anything but.

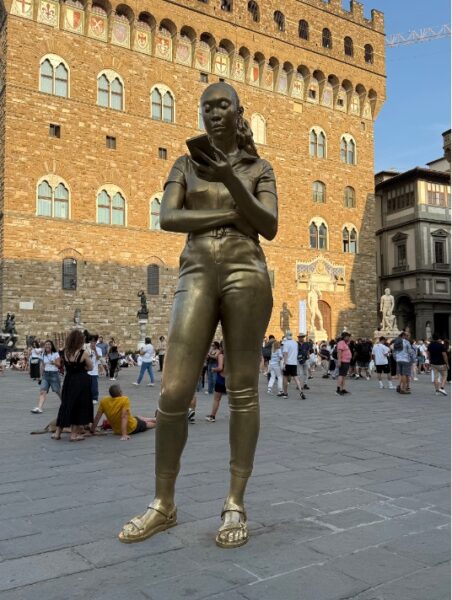

In the shadow of Cellini’s Perseus, sword raised and Medusa’s severed head dangling from his fist, another figure stands — unmoved, unbothered. She’s not carved in marble or myth, but cast in gleaming bronze, her gaze fixed on the phone in her hand, her back turned to the heroic violence behind her. Thomas J. Price’s Time Unfolding disrupts everything about Piazza della Signoria’s iconography. She is anonymous, ordinary, modern — a young Black woman dressed in casual clothes, not armor or robes. In this square long dominated by white, male triumph, her stoic presence asks a different kind of question: Who belongs in public space — and who has always been left out?

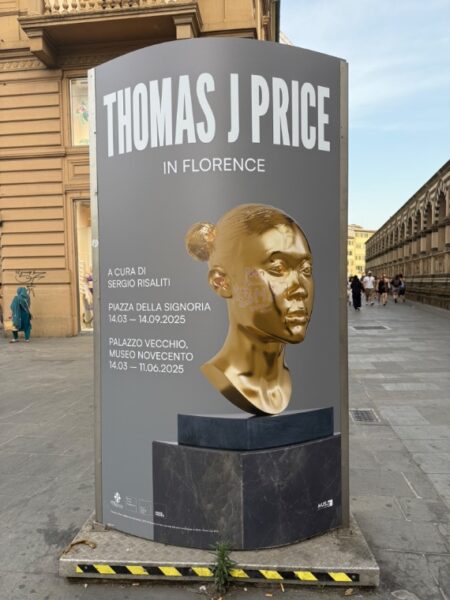

Oversized, contemporary, and defiant, Time Unfolding draws immediate attention—not through grandeur or violence, but through contrast. Her presence has sparked conversation and even vandalism––two influencers were caught taping bananas to the statue a few weeks after her debut. Installed in March 2025 by Museo Novecento, Thomas J. Price’s Time Unfolding doesn’t just introduce a contemporary sculpture into a Renaissance space; it introduces a new set of values into a space historically defined by conquest, idealization, and exclusion.

Price has made a career of planting anonymous Black figures in public—ordinary individuals rendered monumental to “highlight the intrinsic value of the individual and subvert hierarchical structures,” as the Museo Novecento press materials explain.

As tourists pause to take selfies and locals debate whether she belongs at all, the statue has become more than public art; it’s a flashpoint. She raises urgent questions about representation in public space: Who gets to be monumental? Who is granted space to simply exist?

“This is a very significant square in Florence,” said Kai Tossi, 20, a local Florentine. With its copy of Michelangelo’s David, Hercules, and Cellini’s Perseus, the piazza has long served as a stage for Renaissance ideals. But to Tossi, Thomas J. Price’s Time Unfolding belongs here just as much as the others. “You don’t see a lot of women statues,” he said. “It reminded me of inequality, because I never see female statues.” What stands out to him is not just the representation, but the subtle power of presence. “It’s for representation and visibility,” he said. “The statue brings a figure that has been excluded from prominent public spaces.” To him, its placement in the center of a square built on power and patriarchy is intentional and overdue. “For one it’s diverse, for two it’s absolutely beautiful, and for three it’s different.”

For some, that presence is powerful. For others, it feels disruptive. “Shit,” said Simon Fiesoli, 26, a server at a restaurant in Piazza della Signoria, when asked his first impression. “It blocks the square, blocks the view. The other statues are amazing—but only that one is horrible.” To Fiesoli, the work interrupts the symmetry and visual harmony of the space, and has “nothing to do” with Florentine culture.

Alessia Aversano, 24, another local Florentine, struck a more reflective tone. “This is not the first statue that has been added,” she said, referencing the rotating contemporary exhibitions that often occupy the center of the piazza. “I don’t really think they do belong to this piazza. I like it when it’s like, of its own.” She noted that Florence’s tight streets and busy city center can sometimes make the square feel overcrowded. “I prefer this piazza when it has more space. I really enjoy when you can step into a large square with nothing in the middle,” she said. While she acknowledged the work might speak to social media culture—“probably talking about us staying on social media all the time”—she didn’t connect with it visually. “It doesn’t match with its surrounding, it looks like an AI giant.” Still, she emphasized that contemporary art can belong here “if you make it worth belonging, also aesthetically.”

Tourists, too, had varied reactions. A trio from Salamanca, Spain—Jorge Rodríguez Niño, 24; Samuel Martínez Santos, 23; and Javier Mateo García, 22—called the statue “ugly.” For them, it didn’t fit the visual or cultural tone of the piazza. “She looks more modern, creating more contrast,” one said. The consensus? “No, it doesn’t fit in with Florentine culture.”

For Martin Skyette Glerup, 22, from Denmark, that contrast was precisely the point. “It was a little bit misplaced, but in some kind of way I liked it,” he said. “It portrays a tendency in tourism, international tourism, where people don’t really see when they visit. They just look at their phones and click on the photo button, it was a really good representation of our time.” He compared it to the other statues: “They tried to express some kind of ideal or gods, but this one portrays the opposite—just some kind of tendency in society.”

His girlfriend Elinor Markussen, 20, was struck by how much it stood out. “All the other statues are marble, but this one is different,” she said. Positioned directly in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, “you can’t miss it.” At first, she said, the figure seemed like “just a regular teenage person,” but over time it made her reflect on her own behavior. “I thought about it, and now I really want to pay attention to this story. I don’t want to stay looking at my phone.”

For some visitors, the statue’s modern posture raised questions. “Why is she just looking at her phone?” asked Kevin Kraus, 61, from Alabama. He pointed to the other figures nearby and concluded, “No––that’s the Florentine culture.” His wife, Trina Kraus, 58, noticed something else: “She was fully clothed, versus the others,” she said. “But I feel like she is still an object because everything is so tight, it’s still objectifying a female more.” And yet, she also reflected that “everyone belongs in public spaces,” and that the meaning of art often lies in its ambiguity. “Anything can be beautiful, anything is art,” she said. “That’s what makes it unique.”

Felix Saller, 32, and Manuel Kröll, 29, from Germany, agreed that the statue “looks a little bit lost. Nobody interacts face to face anymore,” Saller said. “It’s a criticism about modern times.” They weren’t sure it belonged alongside the classical works, but Kröll offered a different reading: “If it fits with the people walking around, then yes. If it fits with the buildings and statues, then no.”

The reactions—admiration, resistance, confusion—reveal more than just aesthetic preferences. In a city where monuments have long answered the question of who belongs in stone, Time Unfolding turns the question back on its viewers: What stories are we willing to share space with? Who do we allow to stand still and be seen?

This article was produced as part of a journalism collaboration with Georgetown University’s study abroad program in Florence.

Discover more from Florence Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.